Roman polytheism does not provide clear-cut answers about the much pondered question of whether or not there is life after death:

“Traditional Pagan culture offered all kinds of views of death and the after-life: ranging from a terrifying series of punishment for those who had sinned in this life, through a more or less pleasant state of being that followed but was secondary to this life, to uncertainty or denial that that any form of after-life was possible (or knowable) … the official state cult did not particularly emphasise the fate of the individual after death, or urge a particular view of the after-life [Beard et al, Religions of Rome 1 at 289-290].”

Traditional views – realms of the dead

The conventional view of life after death in ancient Rome conceived of an afterlife wherein the soul separated from the body and then typically lived on in the underworld kingdom of Orcus (Dis Pater/Pluto). Sometimes the spirits of the dead might return to the world of the living, as either Manes (protecting spirits of the dead) or Lemures (malevolent spirits of the dead). Over time, Roman ideas about the afterlife came to be strongly influenced by Hellenic visions, which were themselves not always uniform. The features most commonly ascribed to the afterlife included descriptions of Hades being surrounded by various rivers, including the rivers Styx, Acheron and Lethe. From this latter river the dead drank the waters so to forget their former lives. Meanwhile they crossed the river Styx by paying Charon the ferryman – thus the dead customarily had a coin placed in their mouths or their hands lest their souls be stranded in limbo. Upon crossing to the other side of the river they were confronted by Cerberus, the three-headed dog, who prevented unauthorised souls from entering or leaving Hades. Once within Hades, the earthly behaviour of the dead was judged by Minos, Rhadamanthys and Aecus, to determine their fate in the next life. War heroes went to the paradisiacal Elysium, as did, by some accounts, the virtuous. Those guilty of hubris or other behaviour deemed particularly offensive to the Gods might find themselves in Tartarus: a place of divine punishment apparently inhabited by only the most unfortunate of criminals. Meanwhile most of the dead were thought to dwell on in the Asphodel fields, which was neither particularly pleasant nor unpleasant.

There was a belief in heaven, but it was not, as we might expect, a place of reward for pious believers. Cicero described such a place:

“all those who have protected or assisted the fatherland, or increased its greatness, have a special place reserved for them in heaven, where they may enjoy perpetual happiness … it is from heaven that the rulers and preservers of the cities come, and it is to heaven that they eventually return [Cicero, cited in Beard et al, Religions of Rome 2 at 220-221].”

The implication is that heaven is the place where Gods live – thus one needed to be a God, or become a God, to go there. Unlike the Abrahamic monotheists who dominate our own times, Romans did not generally revere the Gods in the hope of securing a good result in the afterlife. More commonly they prayed for health, safety, success and prosperity in the world in which they actually lived, rather than in some nebulous world that may or may not exist after death. Ambivalence about and disbelief in the afterlife was common:

“Many funerary inscriptions of the imperial age testify to the spread of Epicurean beliefs among the common people. Formulae such as non fui, fui, non sum, non desidero (‘I was not, I have been, I am not, I do not want’ …) were so frequently used that they were abbreviated. For instance NF NS NC signifies non fui, non sum, non curo (‘I was not, I am not, I do not care’…). A Latin inscription from Rome reports a Greek text in which is unveiled the truth about the after-life: ‘Do not go forth nor pass along without reading me; but stop, listen to me and do not leave before you have been instructed: there is no crossing ferry to Hades, nor Charon the ferryman, nor Aeacus holding the keys, nor the dog Cerberus’ [Rüpke, A Companion to Roman Religion at 379].”

Epicureanism – no life after death

Disbelief in the afterlife was so common that when Caesar was pontifex maximus (high priest – the most important religious position in Rome) he was able to argue:

“Death is not a torment but a relief from suffering; it is the end of all human misfortune, beyond which there is no place for grief, or joy [Sallust citing Caesar, cited in Kamm, The Romans at 98].”

Ironically, Caesar himself was thought to have joined the ranks of the divinities upon his death and was thus deified by the senate of Rome. This outcome was seemingly in conflict with his apparently Epicurean beliefs (although it is not certain that Caesar was a card carrying Epicurean) – conscientious Epicureans argue that the Gods do not play a role in human affairs; instead they live a life of supreme happiness and tranquility. Within this framework the Gods are ethical ideals, whose lives we should strive to emulate. Epicurus taught that the best kind of life is one lived without fear, anxiety or desire. Such a life would effectively equate to that of a God’s, and would be both tranquil and pleasurable.

Meanwhile humans, as compounds of atoms, are considered to be both mortal and material; ultimately our atoms dissolve following death … kind of. Lucretius (a Roman poet and Epicurean philosopher who died in 55 BCE) clarifies the Epicurean position on life after death:

“nature dissolves all things in turn into their constituent atoms and never reduces anything to nothing … all things are composed of imperishable particles, nature does not allow any compound to disintegrate until it meets a force that shatters it with an external blow or penetrates the spaces between the atoms and unravels it from within.

Moreover, if time, which removes compounds from our sight when they get old, annihilated these compounds by destroying all their matter completely, from what matter does the power of procreation continue to bring the various species of animals into the light of life? … therefore things cannot be reduced to nothing … things which we see now do not ever perish completely, because nature builds up one thing from another thing, and does not compound to be born unless aided by the death of another compound …

Death does not destroy compounds by annihilating the individual atoms; it simply breaks up the compound and releases the atoms. Then it joins each atom to some other atoms … the universe is continually being renewed; and mortals exist through successive exchanges of atoms. One race grows up even as another wastes away, and the generations of living things come and go in brief spans of time; and like runners, they pass on the torch of life [Lucretius, cited in Shelton, As the Romans Did at 422-424].”

Stoicism – the afterlife is unknown

While Epicureans hold that life is merely a random or chance convergence of atoms, and death is but the dispersion of atoms, Stoics (of which Seneca and Marcus Aurelius are the most famous adherents) believe there is a single divine and inherently rational will, which can be called God or Nature or Reason. Since a person’s soul is part of this plan happiness can only be attained when people allow reason to govern their lives and are thus in harmony with the universe (Shelton, As the Romans Did at 426). Stoics believe in a soul which is distinct from the material body:

“My body is that part of me which can be injured; but within this fragile dwelling-place lives a soul which is free. And never will that flesh drive me to fear, never to a role which is unworthy of a good man. Never will I tell lies for the sake of this silly little body … Even now, while we are associated, we will not be partners on equal terms, because the soul will assume all authority [Seneca the Younger, cited in Shelton, As the Romans Did at 428].”

Within this scheme the Gods are regarded as higher, virtuous beings who can help and instruct men and women on the the best way to live a virtuous life, which equates to a happy life:

“in dealing with good men, the Gods follow the same plan that teachers follow in dealing with their students: they demand more work from those in whom they have the most confidence and hope … The demonstration of one’s virtus [virtue, strength, worthiness] is never an easy thing. Fortune beats and lashes us, but we should patiently endure. This is not cruelty, but a contest, and the more often we enter, the stronger we will be [Seneca the Younger, cited in Shelton, As the Romans Did at 430].”

Marcus Aurelius expanded on the theme of the Stoic view of the relationship between people and Gods:

“He is living with the Gods who continuously displays his soul to them, as content with what they have apportioned, and doing what is willed by the spirit … this spirit is each person’s mind and reason … why not rather pray for the gift of not fearing … or of not feeling grief … rather than that any one of them should be absent or present … This man prays: “how may I sleep with that woman?’ You should pray: “how may I not desire to sleep with that woman?’ [Marcus Aurelius, cited in Beard et al, Religions of Rome 2 at 357-358].”

While Stoicism offers a comprehensive vision on the best way to live, the Stoic vision of death is much more hazy. Lactantius, a Christian critic of Pagan thought, stated that Stoics (and Pythagoreans) believe:

“the soul survives after death … since they feared the argument by which it is inferred that the soul must necessarily die with the body, because it is born with the body, they asserted that the soul is not born with the body, but rather introduced into it, and that it migrates from one body to another [Lactantius: Ch XVIII].”

Despite this statement, it seems Stoics have no definitive belief in an afterlife, even though they are supremely conscious of themselves as:

“members of a divine organism … Like the microcosm, the living universe was thought to have an eternal cycle of change. There will come a period … when everything is converted to the divine fire, becomes soul only … Then the fire in turn becomes a wet mass from which the seeds of reason initiate an identical cycle [Urmson and Ree (eds), The Concise Encyclopedia of Western Philosophy and Philosophers at 308-309].”

For a contemporary Stoic (and polytheistic) perspective on life after death see What Really Happens When We Die? by M Horatius Piscinus.

Neoplatonism – reincarnation until unification with the “One”

While Epicureanism and Stoicism were popular during the early imperial era, the philosophical school which dominated Pagan thought in the 4th and 5th centuries was Neoplatonism – until the Platonic Academy was forcibly closed by the Byzantine emperor Justinian in 529 CE, as part of a wider persecution of Paganism. Ironically, centuries later, Neoplatonism would be adapted by Christian and Islamic thinkers into Abrahamic theology.

Neoplatonism is a pantheistic philosophy that espouses belief in a supreme deity who is the source out of which everything, including the Gods (and all other living things), flow. The goal of life therefore is, or should be, to unify with this “One”, via spiritual ascension, and this can be achieved through restraint, virtue and the realisation that:

“you are everywhere at once, in the earth, in the sea, in heaven. You are not yet born, you are in the womb, you are old, a youth, dead, in an afterlife. Realise all of these things simultaneously, all times, places, things, qualities, and you can realise God [Plotinus, cited in Rappe, Reading Neoplatonism at 111].”

That quote is by the traditional founding father of Neoplatonism – Plotinus, a Greco-Egyptian who lived most of his life in Rome and died in 270 CE. As for the afterlife, Plotinus held that:

“a soul takes more than one embodied human lifetime to ascend. Hence the doctrine of reincarnation and providential retribution; the human soul survives death and becomes reincarnated according to what the person has accomplished in this life – whether and to what extent she has actualised her lower or higher nature in the previous life or lives. In the course of reincarnation, the soul gradually prepares itself for a discarnated existence. This is a true ascent, after which the soul will no longer be incarnated in any body, but rejoins the bliss, wisdom and eternal perfection of its source [Remes, Neoplatonism at 119].”

Within this scheme the Gods are beings who are necessarily more ascendant than humans – unlike the Gods of Epicureanism, but similar to the Gods of Stoicism, Neoplatonism holds that the Gods may and do intervene in human affairs, but that their benevolence may depend on the soul of the seeker (Remes, Neoplatonism at 171).

Mystery religions – different visions

Epicureanism, Stoicism and Neoplatonism were the most popular philosophical schools during the Roman era but they were not the only philosophical schools, nor was philosophy the only means by which Roman attitudes to death and the afterlife were defined. A number of mystery religions offered alternative views on the meaning of life and death, however, most revealed their mysteries only to the initiated and each path offered different perspectives so it is not possible to generalise about their visions of the afterlife, even if we had enough information about them to do so:

“In the earlier part of the twentieth century, it was fashionable to [suggest] … that the mystery cults offered their initiates a secure place in the afterlife … This idea has been criticised … For one thing, the different mystery cults do not all seem to offer the prospect of a life after death … Each of them seems rather to have had its own pattern of revealing a mystery and rewarding initiates … [for example, in Mithraism] the progress of the initiate through different phases of revelation seems to be mirrored by the progress of the soul through the stages of the celestial sphere [North, Roman Religion at 69-70].”

Beard et al add:

“Some of the new cults … constructed death much more sharply as a ‘problem’ – and, at the same time, offered a ‘solution’. Certainly, not all the new cults promised life after death; in the case of Jupiter Dolichenus, for example, there is no evidence to suggest that immortality was an issue. And those religions that did make claims about a future life after death presented radically different pictures [Beard et al, Religions of Rome 1 at 289-290].”

Some of the major polytheistic mystery religions of the Roman period were:

- Dionysian (from Greece – focused on the death and rebirth of Dionysus’/Bacchus’ grapevines; women are known to have been keen participants).

- Eleusinian (from Greece – focused on Persephone, Demeter and Hades; and the cycle of life and death).

- Isiac (from Egypt – focused on Isis, her husband Osiris and son Horus; very popular in the 1st and 2nd centuries, especially with women; promised resurrection after death and a blessed afterlife).

- Jupiter Dolichenus (from Syria – especially popular with the military).

- Magna Mater (from Anatolia – focused on Cybele; particularly attractive to women (and MTF transsexuals); focused on the death and resurrection of Cybele’s consort Attis).

- Mithraic (from Persia – focused on a Romanised interpretation of Mithras; especially popular with the military).

- Orphic (from Greece – focused on Orpheus and prescribed an ascetic lifestyle in order to reach Elysium after death and avoid the infliction of afterworld punishments).

Conclusion

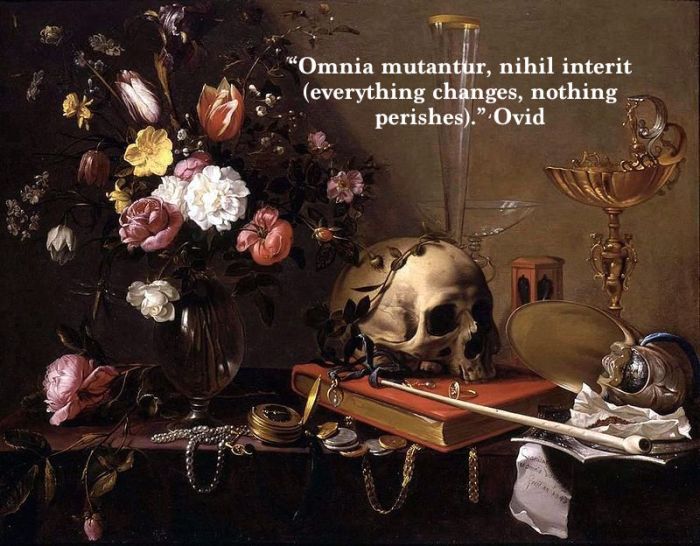

The wide variety of beliefs in ancient Rome about the afterlife (or lack thereof) leaves the door wide open for Roman polytheists to adopt just about any vision of life after death one can conceive of. All that can be said with certainty is that death is inevitable – memento mori.

Sources:

- M Beard, J North and S Price, Religions of Rome: Volume 1: A History, Cambridge University Press

- M Beard, J North and S Price, Religions of Rome: Volume 2: A Sourcebook, Cambridge University Press

- A Kamm, The Romans: An Introduction (2nd ed), Routledge

- J North, Roman Religion, Cambridge University Press

- S Rappe, Reading Neoplatonism, Cambridge University Press

- P Remes, Neoplatonism, University of California Press

- J Rüpke, A Companion to Roman Religion, Wiley

- J Shelton, As the Romans Did: A Sourcebook in Roman Social History (2nd ed), Oxford University Press

- J Urmson and J Ree (eds), The Concise Encyclopedia of Western Philosophy and Philosophers, Routledge

- Encyclopaedia Britannica – britannica.com

- Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy – iep.utm.edu

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy – plato.stanford.edu

- St Takla Haymanout Coptic Orthodox Church Alexandria (Early Church Fathers online) – st-takla.org

Appendix – Roman funerary customs

Much of what we know about ancient Roman funerary customs relate to the aristocratic dead. Lying in state, elaborate funeral processions – complete with chariots, hired musicians and professional mourners, the making of death masks, being laid to rest in a mausoleum, etc are more than most of us can expect. For ordinary Romans we know that their bodies would typically be either buried or cremated outside the walls of the city, alongside personal items such as jewellery, eating and drinking vessels, pottery, dice, toys, etc. Where they were wealthy enough to have tombstones it was not uncommon for the information inscribed thereon to include information about the deceased that would be offbeat by today’s standards. A husband might praise his wife’s virtues and list them, or a child’s personality would be described, or the reader might be encouraged to live life to the full (“do not refrain from the pleasures of love”), or the deceased might proclaim his or her belief in the philosophical teachings of Epicurus (“I didn’t exist, I did exist, I don’t exist, I have no cares”). It was important to many Romans that they be afforded proper funeral rites, and we know that even people of modest wealth, including slaves, joined funeral clubs to ensure a decent funeral (yet many others died impecunious and were either buried in a mass grave or burnt at a public crematorium). This was not just about ensuring dignity after death, appropriate funeral rites were thought to improve one’s prospects in the afterlife, including minimising the chance of departed spirits becoming lemures – malevolent spirits of the dead.

Professor Toynbee writes:

“All Roman funerary practice was influenced by two basic notions – first, that death brought pollution and demanded from the survivors acts of purification … secondly, that to leave a corpse unburied had unpleasant repercussions on the fate of the departed soul …

When death was imminent relations and close friends gathered round the dying person’s bed to comfort and support him or her … The nearest relative present … closed the departed’s eyes … The next act was to take the body … and to wash it and anoint it. Then followed the dressing of the corpse … the laying of a wreath on its head, particularly in the case of a person who had earned one in life, and the placing of a coin in the mouth to pay the deceased’s fare in Charon’s barque …

… the great majority of people in the Roman world were laid to rest in tombs of very varied types strung along the roads beyond the city gates [it was considered both sacrilegious and inauspicious to build a home and hence live near the place of the dead] …

As regards inhumations, the poor were laid directly in the earth … the moderately well to do [were placed] in less elaborate sarcophagi …

[As regards cremation, the] burning of the corpse, and of the couch on which it lay, took place either at the place in which the ashes were to be buried … or at a place specially reserved for cremations … The eyes of the corpse were opened when it was placed on the pyre, along with various gifts and some of the deceased’s personal possessions. Sometimes even pet animals were killed round the pyre to accompany the soul into the afterlife. The relatives and friends then called upon the dead by name for the last time: the pyre was kindled with torches; and after the corpse had been consumed the ashes were drenched with wine. The burnt bones and ashes of the body were collected by the relatives and placed in receptacles … According to their nature and the status of the dead whose remains they held, these receptacles could be either set up free standing inside … tombs, … or … placed in the niches and recesses in the walls of columbaria … or … they could be buried in the earth … [Toynbee J, Death and Burial in the Roman World, Cornell University Press at 43-50]”

Professor Scheid adds:

“In a ceremony observed by more or less all families, the bodies of the deceased were taken to a cemetery situated outside the city, stretching along the roads leading out of town and particularly clustering near the gates. At country houses, the cemetery was found at the boundary of the occupied land or at the side of a nearby road. The funeral rites were celebrated in the necropolis, in front of the tomb … After a period in archaic times when cremation was favoured, the prevailing fashion in the sixth century BC came to be burial. In the first century BC cremation again became widespread – before giving way to burial once more in the second half of the second century. These variations did not [seem to] depend on any particular shift in belief, but were somehow linked to developments within traditional practice … even in cases of cremation, it was still customary to bury what was left of the body, so that a tomb existed according to sacred law. All that changed was the destroying of the corpse … Sometimes that task was left to fire, sometimes to the earth …

[The funeral ritual, which typically included the sacrifice of a pig or other animal victim, proclaimed the status of the dead as one of the Di Manes – protecting spirits of the dead] and the offerings made to the deceased and to his manes (wine, oil, perfumes) were burnt … on the pyre or in a fire next to the tomb. The relatives of the deceased did not share this meal, thereby marking the distance that now separated them from the dead … When the fire was extinguished, the bones and ashes were collected up, washed in wine, and placed in an urn, which was deposited in the tomb …

During the period of mourning, the family of the dead person was considered ‘soiled’ (funestatus) and its members adopted a degraded and disheveled appearance. They wore dark clothes and stopped combing their hair and shaving … once funeral rites had been celebrated, the mourning family gradually returned to normal life …

This set of rites varied from one period to another, and from one place to another … although the ritual was very similar for all families, particularly in the same period and the same region, it was never absolutely identical. Each paterfamilias decided for himself which customs to observe and, in doing so, would obey family traditions rather than prescriptions laid down by the priests … these rituals produced countless variants while remaining within the framework of a common tradition … [Scheid J, An Introduction to Roman Religion, Indiana University Press at 167-169].”

Written by M’ Sentia Figula (aka Freki). Find me at neo polytheist and romanpagan.wordpress.com